Jul-21-2008

The Truth About “The X-Files”

Taki’s Magazine

Tom Piatak

[Original article here]

One of the most accurate assessments ever offered by a government official came when FCC chairman Newton Minow’s described television as a “vast wasteland,” a depiction that has, generally speaking, grown only more accurate since Minow spoke those words in 1961. Today, most programs on television are either vapid or subversive of traditional values—or sometimes both. Rare indeed have been programs of exceptional quality, rarer still those that dissented from the liberal consensus of the day.

One of the few programs in recent years that managed to offer quality entertainment while also suggesting that the Left might not be right was “The X-Files.” The series went off the air in 2002 after a nine-year run, but is still being rerun and might gain a new generation of fans through the release this Friday of the second “X-Files” movie, “I Want to Believe,” which I am eagerly looking forward to. I only regret that I will not be able to hear the thoughtful analysis of the film from a man I had the pleasure of discussing many of the show’s episodes with, and who would always ask to borrow the tape I made of any installment he happened to miss, the great conservative writer and thinker Sam Francis.

Sam was a knowledgeable fan of science fiction and horror, and he recognized “The X-Files” as a superior example of the genre. The show was consistently well acted, and featured intelligent, well-written stories, and production values equivalent to those of most feature films. The series’s central characters, FBI agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully (played by David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson), were attractive, intelligent, enterprising, and likable, and the supporting cast was superb as well. These were the principal virtues of the series, which could be enjoyed by people of all political persuasions.

But there were hints in “The X-Files” of a worldview far closer to paleoconservatism than is generally found in anything emanating from Hollywood. Sam had in fact been put off by the liberal plot lines he found in other fine examples of television science fiction, such as the “Twilight Zone” or the original “Star Trek.” Unlike those series, “The X-Files” had a certain conservative sensibility, offering no vision of “utopia” or even progress in the human condition. It’s telling that the first “X-Files” movie bore the reactionary title “Fight the Future.”

Rather than guiding the way to a brighter tomorrow, Mulder and Scully face the same fundamental problems human beings have always faced, including the persistence of evil. The aliens and monsters who appeared in so many episodes were not benevolent or even misunderstood but implacable foes who needed to be stopped. There was no hint of moral relativism: The serial killer Donnie Pfaster is shown morphing into a demon or other serial killers as he goes about his work, and those who misunderstand the nature of evil get what they deserve. In the first season episode “Tooms,” a social worker accepts a serial killer’s claim that Mulder had brutalized him, and then attempts to befriend him, only to become the killer’s next victim. And almost every episode featured the tagline “The Truth Is Out There,” meaning not only that the truth might be found in unusual places but that there was in fact an objective truth that could be found, despite what the postmodernists want us to believe.

A recurrent theme of the show was that the government can not be trusted. Mulder and Scully weren’t just chasing dangerous aliens but aliens in league with a conspiracy in the federal government and United Nations. The conspiracy is willing to do anything to further its objectives, including killing, lying, and engaging in massive surveillance of the American people. “The X-Files” gave new meaning to the derisive slogan, “We’re from the government, and we’re here to help.” There were episodes devoted to government attempts at mind control, government use of bioweapons against its own citizens, and government medical experiments on unwitting Americans.

As Scott Richert put it in “Us vs. Them,” from Chronicles in ’97, “The X-Files” achieved success “not because of any popular fascination with aliens, but because, after Ruby Ridge, Waco, Whitewater, Vince Foster, Mena, NAFTA, and GATT, Americans have every reason to believe that their government is being run with a callous disregard for their rights and welfare and for the enrichment of an entrenched ruling class.” In fact, as Richert noted in that article, the show even featured an episode, “Unrequited,” that showed the members of a right-wing militia as being both heroic—they had rescued MIAs left behind in southeast Asia by the government—and truthful—the militia leader is the only one who tells Mulder and Scully about the assassin who’s killing the military officers who had signed off on the decision to abandon him and his comrades in Vietnam. How many other TV shows ever cast a militiaman in a positive light?

Bill Clinton once affirmed that you could not both love your country and hate your government, a remark Sam observed was worthy of Brezhnev. It’s obvious why Sam was such fan of “The X-Files.”

However distrustful Mulder and Scully were of the government for which they worked, they never lost faith in America. Scully was the dutiful daughter of a Navy officer, and the boss and protector of Mulder and Scully at the FBI, Walter Skinner, was a proud Marine veteran of Vietnam. (Sam thought it significant that Mulder and Scully worked for the FBI, a bastion of Middle America, rather than the far more elitist CIA). That there is no contradiction between distrusting the government and loving America was brought home in “Jump the Shark,” the final episode featuring the Lone Gunmen, three freelance conspiracy theorists who kept tabs on government misdeeds and often aided Mulder and Scully.

In “Jump the Shark,” the three freely sacrifice their lives to stop a terrorist intent on unleashing a biological weapon and killing thousands of innocent people, causing one of their former adversaries who had worked with the conspiracy to describe them as “patriots” and prompting Skinner to “pull some strings” and get the trio buried at Arlington. As Scully observes at the burial, “like everyone buried here, the world’s a better place for their having been in it.” The love for America evident in those lines is as genuine as the distrust of the government.

“The X-Files” was also largely (though not entirely) devoid of the leftist themes that regularly appear in so much popular entertainment, such as a focus on the glories of multiculturalism and the evils of discrimination. In fact, the show eschewed the de rigueur multiculturalism which dictates that every scene (except ones depicting villains) be carefully integrated and that minorities show up as computer geniuses and the like in vastly greater numbers than in the real world. In many, perhaps most, of the show’s episodes all the characters were white, the minority characters who appeared in the show, just like the white characters, ranged the gamut from the morally ambiguous (Deputy Director Kersh, Mulder’s informant “X”) to the heroic (Agent Reyes), and there were no anguished discussions about race or discrimination.

What the series showed in terms of encounters between the established American culture and immigrant cultures also deviated from the standard multiculturalist script in which Americans are either oppressing immigrants or being enriched by them. In “Hell Money,” a Chinese doctor exploits his fellow immigrants by running a rigged lottery in which no one ever wins, but the losers end up being operated on and eventually killed so that their organs can be sold for profit. Even when the lottery is exposed as a fraud, the doctor evades justice because none of the immigrants are willing to testify against him. And a very sympathetic immigrant who has participated in the lottery in the hopes of earning money to treat his daughter’s leukemia (and loses an eye for his efforts) asks his daughter, “Do our ancestors scorn us for leaving our home? Is that why you are sick now?”

Although the immigrant father in “Hell Money” stays in Chinatown, other “X-Files” immigrants do indeed defy standard Hollywood protocol and decide to return home. In “Fresh Bones,” the problem is caused by a Marine colonel overseeing a refugee camp for Haitians. The colonel fully embraces multiculturalism to the point of becoming a practitioner of voodoo and actually holds the Haitians in North Carolina against their will until the leading priest reveals all his secrets. The problem is solved when the Haitians return to Haiti, after the colonel loses a voodoo contest with the Haitians’ leader and ends up buried alive.

In “El Mundo Gira,” Eladio Buente, a Mexican farmworker in California is exposed to an extraterrestrial enzyme and begins to spread a disease that kills on contact. He is ostracized by his fellow illegal immigrants as “El Chupacabra,” a Mexican monster in which the immigrants fervently believe. For most of the episode, Buente is also being pursued by a brother seeking vengeance for Buente’s first victim, a woman loved by both men. None of his fellow immigrants is willing to protect him from his brother—even an ostensibly assimilated Mexican-American INS agent—because they all believe that “God curses a man who stands between two brothers.” Like the Haitians in “Fresh Bones,” Buente sees his salvation in returning to his homeland for good. “Diversity is strength,” as we all know, but it’s also clannishness and suspicion of outsiders, voodoo and superstition, and blood feuds.

“The X-Files” was largely silent on the hot button issues of the culture wars, but there were intriguing hints that once again the show’s sympathies were not with the Left. In “Colony,” Mulder and Scully investigate the deaths of abortionists who are not being killed by radical pro-lifers but by an alien bounty hunter. The aliens are using the fetal tissue gathered in this grisly trade to attempt to create an alien-human hybrid that will further their plans to colonize the Earth. The conspiracy, too, is working on creating transhuman hybrids, and for this reason one of its leading members is shown in “Redux II” watching with approval as Iowa Democratic Senator Tom Harkin describes as futile any effort to stop human cloning.

Then there’s the subject of sex, sex, sex—a topic to which much of our popular entertainment devotes endless hours and which “The X-Files” virtually ignored. The friendship between Mulder and Scully did not become a physical relationship until they had worked side by side with each other for many years, and even then the exact nature of their relationship was somewhat mysterious. It was as if each character was on a quest for the truth, and nothing else could take precedence—a chivalric ideal within a culture of “if it feels good, do it!”

This ideal was in fact realized in the case of the Lone Gunmen. In the episode “Three of a Kind,” their leader, John Fitzgerald Byers, is shown dreaming about what life would be like if he were married to Susanne Modeski, a woman he has fantasized about since meeting her nearly a decade before. At the end of the episode, Byers is given the chance to go off with Modeski but, fearing that he would endanger Modeski and not wanting to abandon his friends and their own quest for the truth, he declines to follow the woman he loves, a kind of choice that would have made perfect sense to a member of the Templars or the Hospitallers but that is exceedingly rare in today’s culture.

Perhaps the clearest conservative themes in “The X-Files” emerged in connection with religion. Scully’s Catholicism was the focus of several episodes, and she was depicted as a woman of sincere faith, if not a consistent churchgoer. Two episodes show Scully in the confessional, once after saving a boy who is a stigmatic from a man who was in league with the devil, and again after helping to thwart the devil from taking the souls of four teenage girls, whom Scully comes to believe had been sired by an angel. It’s doubtful a leftist show would ever feature the devil as a real character. It’s even less likely it would depict him occupying the professions he did when he appeared on “The X-Files”: a high school biology teacher (“Die Hand Die Verletzt”), a social worker (“All Souls”), and a liberal Protestant minister who advocates tolerance and opposes fundamentalism (“Signs & Wonders”).

“Signs & Wonders” might be the most reactionary episode in the entire series. Mulder and Scully go to rural Tennessee to investigate a murder, and they immediately begin to suspect Enoch O’Connor, a snake-handling fundamentalist preacher who expelled his daughter and her boyfriend from his congregation when she became pregnant. (Interestingly, in addition to sharing the same last name as the great Southern writer Flannery O’Connor, Enoch has the same first name as a character in O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood and wears old-fashioned glasses reminiscent of the type worn by the writer). When Scully complains to Mulder about O’Connor’s “intolerance,” he replies, “Sometimes a little intolerance can be a welcome thing. Clear cut right and wrong, hard and fast rules, no shades of gray.”

O’Connor’s opponent in the town is a liberal Protestant minister, whose church encourages members to “think for themselves” and “live [their lives] the way [they] want,” and which offers an “open and modern way . . .of looking at God.” Despite the attractiveness of the liberal minister and the rough edges of his fundamentalist counterpart, Mulder and Scully learn in the end that the murders have been committed by the liberal minister to discredit his fundamentalist rival, and the viewer learns that the liberal minister—who disappeared from Tennessee only to become the pastor of a church in liberal Connecticut—is the devil. Sam felt that no other series on TV would have produced an episode that so perfectly transgressed the norms of the liberal Zeitgeist, in which “tolerance” is the supreme good and any Christian who takes the traditions of his own faith too seriously is treated with suspicion at best or hostility at worse.

The religious theme became more explicit in “The Truth,” the final episode of the series. The series ends with Mulder and Scully on the run from the conspiracy and its friends in the government, hiding in a hotel room in New Mexico. These are the final lines spoken in the series:

Scully: “You’ve always said that you want to believe. But believe in what Mulder? If this is the truth that you’ve been looking for, then what is there to believe in?

Mulder: “I want to believe that the dead are not lost to us. That they speak to us as part of something greater than us—greater than any alien force. And if you and I are powerless now, I want to believe that if we listen, to what’s speaking, it can give us the power to save ourselves.”

Scully: “Then we believe the same thing.”

Mulder: “Maybe there’s hope.”

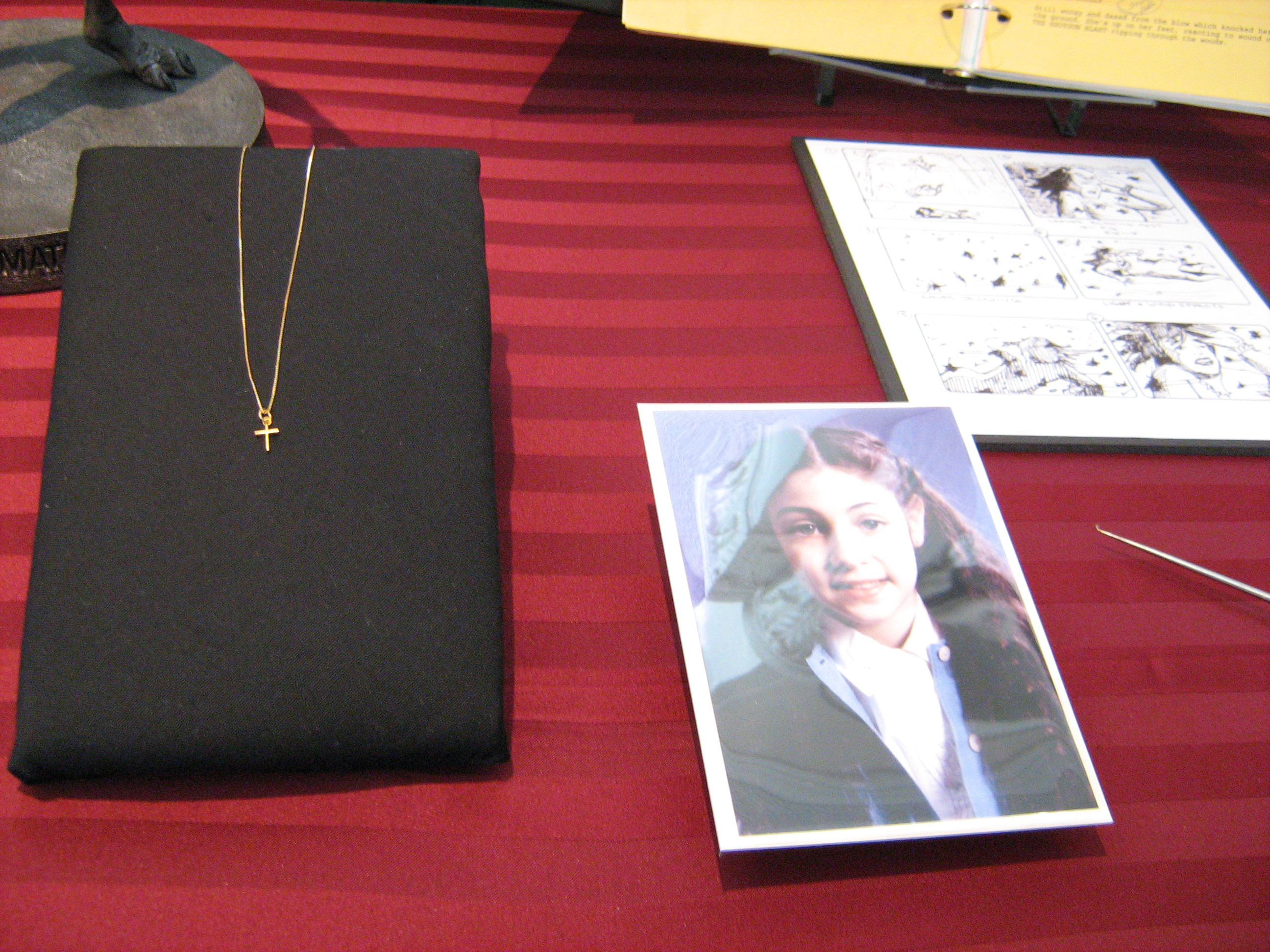

Lest the viewer have any doubt about what is being discussed, the camera zooms in on the tiny gold cross Scully has worn throughout the series. In discussing this ending with Sam, he told me that it contained the most pro-Christian sentiment he had seen in a mainstream television show in some years. “The X-Files” was hardly an apology for orthodox Christianity, and it explored many ways of believing, but its respect for belief certainly encompassed the Western traditions.

It appears that “I Want to Believe” may delve into some of these same themes. The tagline for the movie in its theatrical trailer is “To find the truth you must believe,” which is not that different from Anselm’s credo ut intelligam. But even if my guess about the movie is wrong, and Mulder and Scully end up embracing every leftist shibboleth imaginable, the original series will still continue rewarding intelligent viewers who give it a try, particularly those viewers who believe that the truth is out there, somewhere off to the right.

Tom Piatak is a contributing editor to Taki’s Magazine.

The donated items include a “maquette” (model) of an alien used as a reference point in the first X-Files movie, a stiletto used by characters to exterminate aliens masquerading as people, an “I Want to Believe” poster that appeared in Mulder’s office on the show and is signed by Carter and stars David Duchovney and Gillian Anderson, the annotated script from the very first episode with a page of storyboards, prop FBI badges and business cards, a photograph of Mulder’s sister, Samantha, whose abduction by aliens is the motivation for his work, and the crucifix necklace worn by Agent Scully that symbolized her commitment to her faith.

The donated items include a “maquette” (model) of an alien used as a reference point in the first X-Files movie, a stiletto used by characters to exterminate aliens masquerading as people, an “I Want to Believe” poster that appeared in Mulder’s office on the show and is signed by Carter and stars David Duchovney and Gillian Anderson, the annotated script from the very first episode with a page of storyboards, prop FBI badges and business cards, a photograph of Mulder’s sister, Samantha, whose abduction by aliens is the motivation for his work, and the crucifix necklace worn by Agent Scully that symbolized her commitment to her faith. The creator of the series, Chris Cooper, said, “my love is telling suspense thrillers with smart people and interesting subjects.” He was especially proud of staying with the show throughout its nine years, citing Robert Graves: “one of the hardest energies to find and sustain is maintenance energy,” and remained committed to “creating it anew every week.” He said that one of the best pieces of advice he received was from a production designer who read the original script and told him, “Don’t show them anything. Keep it in the shadows. You will have no time and no money and what they don’t see is scarier than what they do see.”

The creator of the series, Chris Cooper, said, “my love is telling suspense thrillers with smart people and interesting subjects.” He was especially proud of staying with the show throughout its nine years, citing Robert Graves: “one of the hardest energies to find and sustain is maintenance energy,” and remained committed to “creating it anew every week.” He said that one of the best pieces of advice he received was from a production designer who read the original script and told him, “Don’t show them anything. Keep it in the shadows. You will have no time and no money and what they don’t see is scarier than what they do see.” GILLIAN ANDERSON: I wasn’t anxious.

GILLIAN ANDERSON: I wasn’t anxious. DUCHOVNY: I thought I was kind of intrigued by the kernel of the idea that we wanted to keep secret for a long time, which Chris was protective of because he thought – not because he thinks – if you see the movie, if you know it before you see the movie that it’ll ruin the movie. But I think he was afraid that it was something that could be copied and get out there before our movie got out there, and that would take the wind out of our sails. So we effectively got around that. But it was that idea that I’m not talking about that was kind of fascinating and disgusting and horrifying and interesting. I’m speaking about me with my shirt off.

DUCHOVNY: I thought I was kind of intrigued by the kernel of the idea that we wanted to keep secret for a long time, which Chris was protective of because he thought – not because he thinks – if you see the movie, if you know it before you see the movie that it’ll ruin the movie. But I think he was afraid that it was something that could be copied and get out there before our movie got out there, and that would take the wind out of our sails. So we effectively got around that. But it was that idea that I’m not talking about that was kind of fascinating and disgusting and horrifying and interesting. I’m speaking about me with my shirt off. ANDERSON: Well, I actually forgot that I had a baby. When we started shooting somebody had to remind me.

ANDERSON: Well, I actually forgot that I had a baby. When we started shooting somebody had to remind me. DUCHOVNY: I think it’s just like sprinkles on the top in this movie. You know there’s a bunch of kind of winks at the audience. And Chris was very kind of into, you know, having these winks. Not so much me because I always feel like that’s not part of the realism or the drama, you know. You don’t know we’re winking at anybody, but it’s something that fans, I think, enjoy. And I can’t remember any that are actually in it.

DUCHOVNY: I think it’s just like sprinkles on the top in this movie. You know there’s a bunch of kind of winks at the audience. And Chris was very kind of into, you know, having these winks. Not so much me because I always feel like that’s not part of the realism or the drama, you know. You don’t know we’re winking at anybody, but it’s something that fans, I think, enjoy. And I can’t remember any that are actually in it. DUCHOVNY: Oh, yeah. There were no moments when it didn’t.

DUCHOVNY: Oh, yeah. There were no moments when it didn’t.